The pandemic, and the prime minister’s stint in an intensive care unit last year prompted a renewed focus on obesity in the UK. The evidence so far suggests that a high BMI is associated with increased hospital and intensive care admissions and with higher mortality rates. The presence of diabetes further increases that risk due to the inflammatory effects of hyperglycaemia (high blood glucose levels) on the body and the immune system.

This predictably results in sensationalist headlines accompanied by images of headless bodies with rolls of fat spilling out of cheap clothes, and all the usual finger-wagging, moralising, and self-righteous judgement. It’s an age-old tactic used by the tabloid press to garner interest (and sales) by appealing to that ugly side of human nature that likes to take the moral high ground over anyone we perceive as less virtuous than ourselves. But the reality is that this stigma, propagated by the media and consumed by the masses, is harmful to us all. It harms people living with obesity who are publicly vilified and inevitably internalise the toxic message that is it is “all their own fault”, and it harms society as a whole when we fail to challenge the widely held belief that chronic illness is a moral failing.

I get it. I do. It’s an attractive prospect to believe that one’s wellness, or one’s slimness, are due to an innate moral superiority, or that being “brought up the right way” has protected one’s family from cancer, diabetes and obesity. But while it’s true that obesity, like diabetes and a predisposition to certain cancers, often does run in families, the science clearly shows us that this heritability has much more to do with nature, than it does nurture. This was confirmed by research in the 1990s by Bouchard et al, which tracked and compared the BMI of identical and non-identical twins, reared together and apart, and found that identical twins almost always weigh the same, regardless of whether they are raised together or apart with different parents.

It is now widely recognised that genetic predisposition is the single greatest predictor of obesity, and that each of us has a “set-point”, determined primarily by genetics, to which our weight will typically return, due to changing levels of hormones such as leptin and grehlin, following a period of calorie restriction or excess. We have evolved to survive periods of food scarcity, and the body fiercely defends this set-point, particularly when we restrict our intake for weeks or months at a time, resulting in a plateau in weight loss and eventual weight regain.

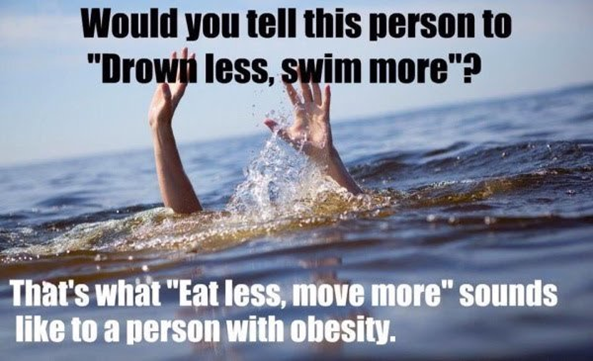

While environmental factors such as the availability of inexpensive energy-dense foods and over-reliance on sedentary forms of entertainment certainly impact on our health and wellbeing, the assumption that weight is a simple issue of “eat less, move more”, is at best factually incorrect and unhelpful, and at worst promotes feelings of shame that prevent people living with obesity from accessing the services that could assist them in losing weight and improving their health.

(James Fell, 2015 – bodyforwife.com)

It’s time we applied the science. We know that diet alone typically doesn’t work, at least not in the long term, and exercise alone certainly doesn’t. We are at a point in time when pharmacological advancements mean we have medications in our arsenal that not only assist with weight loss but when used optimally may also help prevent weight regain and reduce the cardiovascular risks associated with obesity.

It’s time we stopped treating mental health as though our brains are somehow separate from our physical bodies. There is a bi-directional relationship between mental and physical health. Good psychological wellbeing improves our ability to self-care, which is vital when managing a chronic condition like type 2 diabetes or obesity.

It’s time for a less judgemental approach, which prioritises the values and aspirations of the individual, their medical history, their mental health and their overall wellbeing.

In short, it’s time we listened.

References

Yan Y, Yang Y, Wang F, et al (2020). Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with severe covid-19 with diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Research and Care. DOI: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2020-001343

Farias MM, Cuevas AM, Rodriguez F (2010). Set-point theory and obesity. Metabolic Syndrome and Related Disorders. DOI: 10.1089/met.2010.0090. Epub 2010 Nov 30. PMID: 21117971

Bouchard C, Tremblay A, Després JP, Nadeau A, Lupien PJ, Thériault G, Dussault J, Moorjani S, Pinault S, and Fournier G (1990). The Response to Long-Term Overfeeding in Identical Twins, The New England Journal of Medicine. DOI: 10.1056/NEJM199005243222101 322:1477-1482

Wadden T, Hollander P, Klein, S. et al (2013). Weight maintenance and additional weight loss with liraglutide after low-calorie-diet-induced weight loss: The SCALE Maintenance randomized study. International Journal of Obesity 37, 1443–1451. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2013.120

Written by Rosie Joy (ECG Clinical Development Manager ), Thursday 18th February 2021

You can follow me at: https://twitter.com/ECG_Rosie